Dear friends of ÌMỌ̀ DÁRA,

We have some bittersweet news to share with you. After a decade-long journey, we have made the decision to close the current incarnation of imodara.com. It has been an extraordinary experience, beginning as a humble Tumblr blog and growing into a digital resource cherished by African art enthusiasts worldwide. We owe this success to you, our incredible community of art lovers, and we want to express our heartfelt gratitude for your unwavering support.

Throughout the years, we have had the privilege of sharing awe-inspiring art, conducting insightful interviews, garnering recognition in the press, and fostering a vibrant community of individuals passionate about African art. We cannot emphasize enough how much we have learned from you, and your enthusiasm continues to inspire us.

While we bid farewell to this website in its current form, we eagerly embrace the future and the exciting opportunities it holds. Our focus now shifts towards forging innovative connections between African art collectors, esteemed scholars, and renowned dealers in new ways. We are already hard at work on remarkable projects and we cannot wait to unveil them to you. Rest assured, we will return before long, and we sincerely hope you will accompany us on this new adventure.

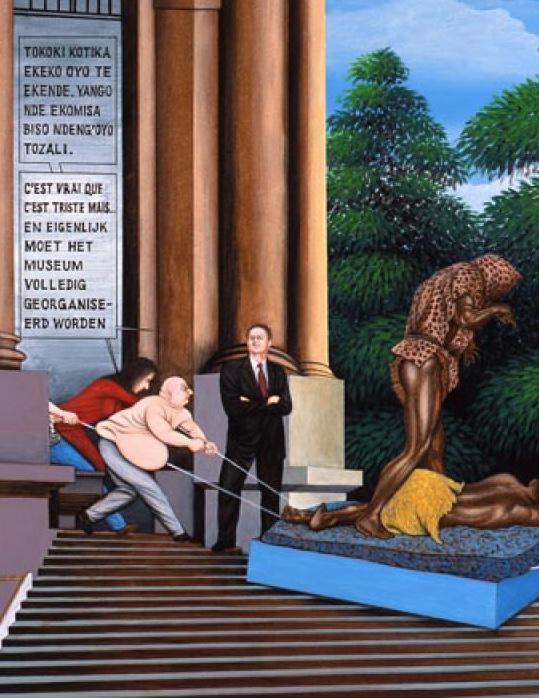

In the interim, we encourage you to stay connected with us. We will continue sharing captivating works of classic art on social media platforms, publishing the bi-annual collector survey, and updating the 'Send It Back' timeline. To stay up-to-date on the latest news, kindly sign up for our mailing list.

Once again, we extend our deepest appreciation for everything. It has been an absolute joy to share the beauty of classic African art with you. Your unwavering support has meant the world to us, and we wish you nothing but the very best.

With sincere gratitude,

Adenike and Jonathan

"ÌMỌ̀ DÁRA is your destination to build your knowledge about the origin, use and distinguishing features of African art pieces"

Yoruba Proverb: Ogbon dùn-ún gbon; ìmo dùn-ún mo | Wisdom and knowledge are good things to have ÌMỌ̀ DÁRA’s mission is to connect art collectors with the world’s leading dealers and scholars, based on a foundation of knowledge; knowledge about the origin, use and distinguishing features of listed pieces. We aim to give collectors unprecedented access to objects, research, cultures and people that matter in African art.